서 론

재료 및 방법

1. 실험재료

2. 유리당 분석

3. 라이코펜 분석

4. 아스코르브산 분석

5. 폴리페놀 분석

6. 항산화력 분석

7. 통계분석

결과 및 고찰

1. 성숙단계에 따른 유리당 함량 변화

2. 성숙단계에 따른 라이코펜 함량 변화

3. 성숙단계에 따른 아스코르브산 함량 변화

4. 성숙단계에 따른 퀘르시트린 함량 변화

5. 성숙단계에 따른 항산화 활성 변화

결 론

서 론

토마토(Solanum lycopersicum L.)는 가지과에 속하는 채소작물로 남미의 고원지대가 원산지인 것으로 알려져 있으며, 우리나라에는 17세기 초 청나라로부터 전래된 것으로 알려졌다. 2021년 기준으로 우리나라의 토마토 시설재배 면적과 생산량은 각각 6,010ha와 369,383톤으로 2019년의 5,706ha와 358,580톤에 비해 다소 증가하였다(MAFRA, 2021). 토마토 과실의 품질은 다양한 요인에 의해서 결정되는데, 특히 과피색, 크기, 모양 등의 형태적인 특징과 유리당, 유기산, 생리활성 물질 등의 기능성의 특징에 영향을 받는다. 토마토는 소비되는 용도에 따라 가공용과 생식용으로 분류하며, 특히 과실의 크기에 따라 완숙 토마토와 같은 대과종 그리고 방울 토마토와 같은 소과종으로 분류하기도 한다. 또한 소비자들의 건강에 대한 관심과 함께 다양한 색의 토마토를 선호하는 현상에 따라 흑색, 황색 그리고 적색 등의 다양한 과피색을 갖는 토마토가 육성되어 시판되고 있다.

토마토의 맛을 결정하는 주요 물질인 유리당의 함량에 따라 단맛의 차이가 크며, 이에 따라 품질이 좌우되는데, 과실의 유리당은 주로 자당, 과당, 그리고 포도당으로 구성된다(Lee 등, 1972). 과실의 당 함량은 광합성기관에서 유래된 자당의 가수분해와 환원당의 과실 내로의 축적으로 결정되며(Ho, 1979), 토마토의 품종 및 재배 환경에 따른 차이가 크다(Lee 등, 1972). 토마토 과실의 주된 당원은 과당과 포도당인 것으로 보고되는데, 토마토 과실 건물중의 약 50% 정도가 과당과 포도당이다(Davies와 Hobson, 1981). 토마토 내실 내의 당 함량은 과피가 착색되면서 증가하기 시작해서 완숙기에 가장 높은 것으로 알려져 있다(Beltran와 Macklin, 1962).

토마토 과실의 대표적인 기능성분으로는 라이코펜과 아스코르브산인 것으로 알려져 있으며(Danuta 등, 2020; Li 등, 2021), 라이코펜은 활성산소를 제거하는 항산화 작용 능력이 크며(Hwang와 Bowen, 2004; Kim, 2010; Muller 등, 2016; Li 등, 2021), 항산화 작용으로 활성을 잃은 라이코펜을 다시 항산화 활력을 갖는 상태로 되돌리는 역할은 아스코르브산이 관여된 것으로 알려져 있다(Rao, 2006). 이처럼 토마토의 항산화 능력과 관련된 영양학적 특징(Toor 등, 2006)이나 라이코펜(Javanmardi와 Kubota, 2006; Bravo 등, 2012; Farneti 등, 2012; Vallverdú-Queralt 등, 2013), 폴리페놀 함량(Luthria 등, 2006; Liu 등, 2009)에 대해 기능성 연구들이 많이 진행되었다.

수용성의 아스코르브산은 유산소 생활에서 항산화 물질로 식물, 동물 및 균류를 포함한 생명체에 전반적으로 존재한다(Wheeler 등, 1998; Mellidou와 Kanellis, 2017; Davey 등, 2000), 식물, 동물 및 광합성을 하는 원생동물 사이에는 아스코르브산 생합성 경로가 다르게 작용하며, 균류는 아스코르브산의 5탄당 유도체인 D-에리트로아스코르베이트를 합성한다(Smirnoff, 2018). 식물에 존재하는 아스코르브산은 환원형과 산화형의 2가지 형태로 육탄당의 유도체이며(McDowell, 1989), 아스코르브산은 수용성의 기능성 물질로 활성산소종을 무독화시켜 산화적 피해로부터 DNA, 단백질 및 지질을 보호하며, 일반적으로 비타민 C로 알려져 있다(Paciolla 등, 2019). 채소를 이용한 식이요법에서 아스코르브산은 암, 심장병, 백내장 및 면역 체계 기능을 포함한 일반적인 퇴행성 질병을 예방하며(Sauberlich, 1994; Howard 등, 2000), 계속적으로 보충을 해야 하므로 섭취를 통해 공급하는 중요한 기능성 물질이다. 또한 생명체 내에서 발생되는 파괴적인 자유 라디칼을 소거하여 세포의 산화를 예방함으로써 세포와 조직을 보호하는 항산화 성분이다(Lee와 Kim, 1989; Howard 등, 1994).

토마토 과실은 영양적인 측면에서 미네랄 뿐만 아니라 비타민 등의 공급원이며(Davies와 Hobson, 1981), 다양한 폴리페놀과 라이코펜 함량이 높은 과실로 식용증진, 피로회복, 혈액순환 개선 등의 생리활성 작용과 함께 폐암, 전립선암 및 위암 등을 예방하는 효과도 큰 채소이다(Davies와 Hobson, 1981).

식물에 함유되어 있는 페놀화합물은 2차 대사산물로 채소작물에서 다양한 구조와 분자량을 갖는다(Kang와 Saltveit, 2002). 또한 페놀화합물은 채소작물의 독특한 과피색을 갖도록 하며, 산화-환원 효소 반응의 기질로 이용되며 미생물로부터 식물체를 보호하는 작용을 한다(Lee 등, 2005). 또한 동시에 쓴 맛과 떫은 맛에 관여하며, 페놀화합물은 수산기를 갖고 있기 때문에 단백질 등의 거대분자들과 쉽게 결합하여 항암 및 항산화 같은 생리활성 작용에 관여한다(Lee 등, 2005). 뿐만 아니라 페놀화합물이 활성산소로부터 발생되는 산화적 스트레스를 감소시켜 만성적인 질병을 예방하는 것으로 보고된다(Kang와 Saltveit, 2002; Chisari 등, 2010). 플라보노이드는 페놀화합물에 속하는 기능성물질로 식물체에 비생물적 환경스트레스 발생 시에 저항성을 증가시켜 식물을 보호하는 작용을 하고, 섭취 시 병원체 등으로부터 인체를 보호하는 것으로 보고된다(Hernández 등, 2009; Treutter, 2010). 페놀화합물은 페놀산이나 플라보노이드 같은 계피산의 유도체나 벤조산 같은 형태로 분류되며, 이러한 페놀화합물의 구조적 특성에 따라 항산화 활성의 차이가 나타난다(Moure 등, 2001). 일반적으로 거대 분자 구조를 갖는 기능성 물질들은 분자 내의 수산기 개수나 위치에 따라 항산화 활력 효과가 달라지는데, 이는 라디칼 소거반응에서 전자의 이동이 페놀화합물의 구조적 특징에 따라 다르기 때문이다(Rice-Evans 등, 1996; Rice- Evans 등, 1997).

활성산소종에서 유래한 자유 라디칼은 작물의 대사작용을 감소시키며(Benson 등, 1992), 세포를 구성하는 다양한 성분인 DNA, 탄수화물, 단백질, 및 지질 등의 세포 구성물질을 손상시킴으로써 산화적 스트레스를 일으킨다(Gill와 Tureja, 2010). 다양한 활성산소종으로 유발되는 산화적 스트레스를 저감하는 항산화 활성은 ABTS나 DPPH 등에 의한 자유 라디칼 소거능력으로 확인할 수 있는데, 딸기(Meyers 등, 2003; Cheel 등, 2007; Fan 등, 2012), 토마토(Choi, 2021), 고추(Akhtar 등, 2018; Howard 등, 2000) 등 다양한 작물의 항산화 능력을 분석하는데 이용된다. 이러한 ABTS와 DPPH 등의 항산화 능력 분석은 방향족 아민류와 항산화제의 환원과 탈색 반응을 통하여 천연물질로부터 항산화 능력이 있는 물질을 찾는데도 이용된다(Kim, 1999). ABTS와 DPPH 소거능이 높은 시료는 ORAC(oxygen radical absorbance capacity) 분석 결과와도 일치하며, 저밀도지단백의 산화를 방지하고 에틸렌 형성물의 유도를 억제하는 효과가 있다(Liu 등, 2007).

토마토의 성숙 단계는 green, breaker, turning, pink, light red, 그리고 red의 단계로 과피색의 변화에 따라 6단계로 구분되며(Choi 등, 2022), 토마토 과실의 성숙 단계별로 기능적 특징이 다른 단백질체의 발현 양상의 차이가 나타난다(Choi 등, 2022). 또한 토마토 과실이 성숙하는 동안 총 페놀함량, 비타민 C, 라이코펜 등의 다양한 생리활성 물질의 함량 변화가 나타난다(Periago 등, 2009).

토마토는 다양한 숙도 따라 다양한 생리활성물질을 형성하기 때문에, 최근 건강에 관련된 기능성물질을 함유한 토마토의 생산은 매우 중요하며, 이러한 토마토 과실의 영양적인 측면에서 기능성 물질에 대한 연구는 중요하다. 따라서 우리나라에서 재배되는 과피색이 다른 토마토의 성숙 시기에 따른 기능성물질의 축적 특징을 분석하여 고품질 토마토 생산과 소비자의 과실 선택을 위한 자료를 제공하고자 한다.

재료 및 방법

1. 실험재료

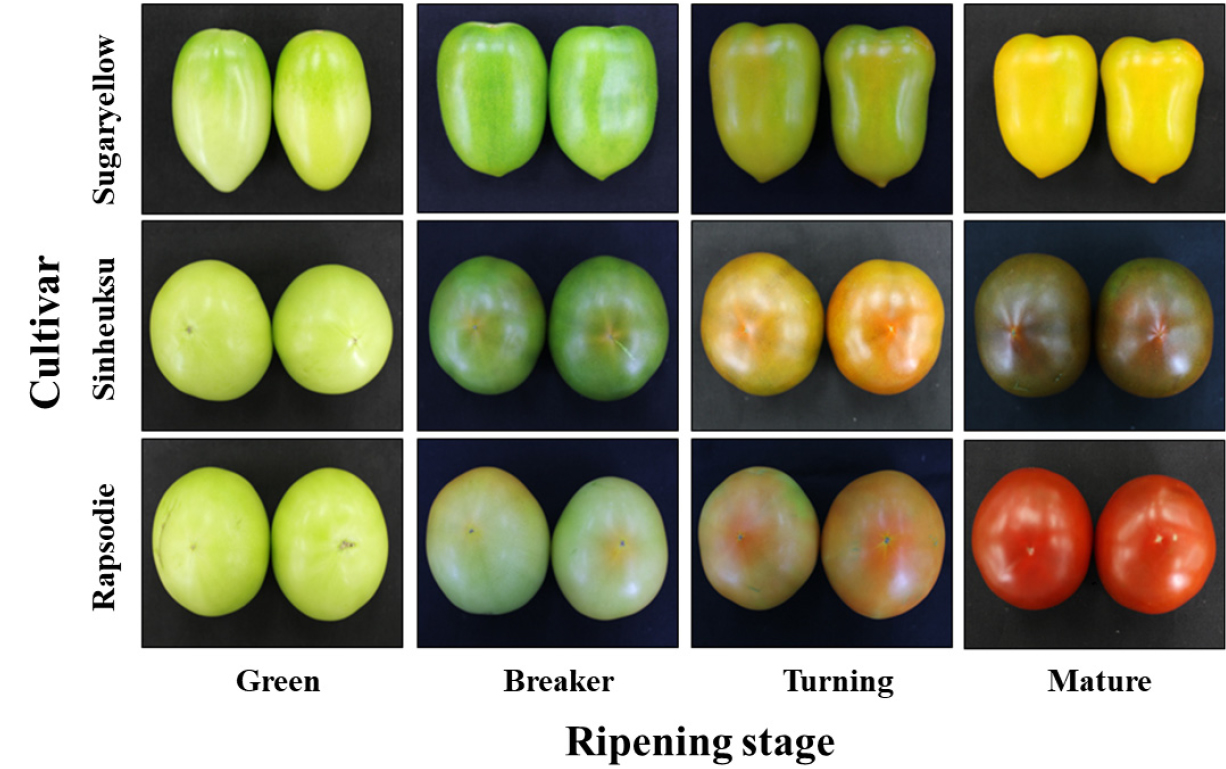

본 실험에 사용한 재료는 토마토의 과피색에 따라 적색 토마토(cv. Rapsodie, Syngenta Seeds Ltd., Korea), 흑색 토마토(cv. Sinheuksu, Asia Seeds Ltd., Korea) 및 황색 토마토(cv. Sugaryellow, Asia Seed Ltd., Korea)를 사용하였다. 종자는 파종하기 전에 종이 필터(Whatman No. 1)가 깔린 직경이 15cm인 페트리디시에 종자를 치상하여 25°C 생장상(HB-103M, Hanbaek Co., Korea)에서 최아시켰다. 최아된 종자는 육묘용 상토(Shinangrow, Korea)로 충진된 파종용 플라스틱상자(45 × 35 × 8cm, 길이 × 너비 × 높이)에 파종하였다. 제1 본엽 또는 2 본엽이 전개되었을 때 상토가 충진된 플라스틱 포트(11 × 11cm)에 가식하였다. 토마토 식물체에서 제1 화방이 전개되기 시작할 때 격리상(300 × 100 × 35cm, 길이×너비×높이) 포장에 정식하였다. 재식거리는 70 × 25cm이고 점적호스 위에 흑색비닐 멀칭하여 재배하였다. 토마토의 수정을 위해서 토마토톤을 10mg·L-1의 농도로 처리하였고, 3화방까지 재배된 토마토 과실을 녹숙기(green, 수분 후 7-10일째), 변색기(breaker, 수분 후 15-20일째), 최색기(turning, 수분 후 25-30일째), 완숙기(mature, 수분 후 35-40일째)로 구분하여 수확한 후 분석 시료로 이용하였다(Fig. 1).

2. 유리당 분석

초저온 냉동고(−70°C)에 보관한 토마토 시료를 균질기(Polytron PT-MR 3100D, Kinematica, Switzerland)로 마쇄한 시료 1.0g을 증류수 10mL과 혼합하여 1시간 동안 80°C 항온수조(WMB-311, Daihan Scientiric Co. Ltd., Korea)에서 반응하여 추출하였다. 이후 원심분리기(Allegra 64R, Beckman Coulter Inc., USA)에 넣어서5분간 15,000×g로 원심 분리한 용액의 상징액 1mL을 acetonitrile 1mL과 혼합하여 0.2μm 주사기 필터로 여과한 후 사용하였다. HPLC(YL12000, Younlin Co., Korea)에 sugar pak(DB-C18, 4.6 × 150mm, Supelco, USA) 칼럼과 RI detector(YL9170, Younlin Co., Korea)로 검출기로 구성된 시스템에서 분석하였다. 이동상으로는 혼합용매(acetonitrile : 증류수, 80 : 20, v/v)를 사용하였고, 유속과 온도는 분당 1.0mL과 25°C로하여 시료를10µL주입하였다. 자당, 포도당 그리고 과당의 표준물질(Sigma-Aldrich Chemical Co., USA)을 사용하였다. 칼럼에 머무름 시간은 과당, 포도당 및 자당에서 각각 2.99, 3.26, 4.19분이었고, 표준검량선의 r2은 0.9997이었다.

3. 라이코펜 분석

초저온 냉동고(−70°C)에 보관한 토마토 시료를 균질기(Polytron PT-MR 3100D, Switzerland)로 마쇄한 후 시료 1.0g을 50mL 튜브에 담아 혼합된 용매(n-hexane, 메탄올, 그리고 아세톤) 20mL과 증류수 10mL을 혼합하여 3시간 동안 반응시켜 추출하였다. 이후 원심분리기(Allegra 64R, Beckman Coulter Inc., USA)로 10분간15,000×g로 반응하여 분리된 상징액 1mL을 0.2μm 주사기 필터로 여과하였다. HPLC (YL12000, Younlin Co., Korea)에 sugar pak(DB-C18, 4.6 ×150mm, Supelco, USA) 칼럼과 DA detector(YL9120, Younlin Co., Korea) 검출기로 구성된 시스템으로 라이코펜을 분석하였다. 이동상(acetonitrile : 메탄올, 85 : 15, v/v)의 유속과 오븐 온도는 분당 1.5mL과 25°C이었고, 시료의 주입량은 20µL였다. 라이코펜(Sigma-Aldrich Chemical Co., USA)을 표준물질로 사용하였고, 크로마토그램 상에 머무름 시간이 9.5분이었고, 표준검량선의 r2은0.9994였다.

4. 아스코르브산 분석

초저온 냉동고(−70°C)에 보관한 토마토 시료를 균질기(Polytron PT-MR 3100D, Switzerland)로 마쇄한 후 시료 1.0g을 15mL 튜브에 0.2M KH2PO4(pH 4.5) 5mL와 같이 1시간 반응시킨 후 원심분리기(Allegra 64R, Beckman Coulter Inc., USA)로 5분간 15,000×g원심분리한 후 상징액 1mL을 0.2μm 주사기 필터로 여과한 후 사용하였다. HPLC(YL12000, Younlin Co., Korea)에 sugar pak(DB-C18, 4.6 × 150mm, Supelco, USA) 칼럼과 DA detector(YL9120, Younlin Co., Korea) 검출기로 구성된 시스템으로 아스코르브산을 분석하였다. 이동상은 A용액(20mM ammonium acetate와 증류수로 만든 0.1% formic acid)과 B용액(20mM ammonium acetate와 메탄올로 만든0.1% formic acid)을 혼합한 것으로, 유속과 오븐 온도는 분당 0.75mL과 25°C이며, 시료의 주입량은 10µL였다. 아스코르브산(Sigma-Aldrich Chemical Co., USA)을 표준물질로 사용하였고, 머무름 시간은 2.28분이었으며 표준검량선의 r2은 0.9998였다.

5. 폴리페놀 분석

초저온 냉동고(−70°C)에 보관한 토마토 시료를 균질기(Polytron PT-MR 3100D, Switzerland)로 마쇄한 후 시료 1.0g을 15mL 튜브에 담아 메탄올 10mL과 함께 5시간 반응시켜 추출하였다. 추출물을 C18, silica(1.0g) cartridge에서 메탄올을 이용하여 용리시킨 후 질소 농축하였다. 건고물을 다시 메탄올 1mL로 용해하여 0.2μm 주사기 필터로 여과하여 사용하였다. HPLC(YL12000, Younlin Co., Korea)에 sugar pak(DB-C18, 4.6 × 150mm, Supelco, USA) 칼럼과 VW detector(YL9120, Younlin Co., Korea) 검출기로 구성된 시스템으로 폴리페놀 화합물 분석하였다. acetonitrile와 증류수(50 : 50, v/v)로 구성된 이동상의 유속과 오븐 온도는 분당 0.7mL과 35°C이며, 시료주입량은 10µL였다. 폴리페놀 분석을 위해 캠페롤, 퀘르세틴 및 퀘르시트린(Sigma-Aldrich chemical Co., USA)을 표준물질로 사용하였고, 머무름 시간은 각각 39.7, 34.3, 26.4분이었고 표준검량선의 r2은 0.9992였다.

6. 항산화력 분석

토마토 시료(3g)과 메탄올(25mL)을 50mL튜브에 담아서 균질기(Polytron PT-MR 3100D, Switzerland)로 균질화한 후 12시간 동안 4°C에서 반응시켰다. 반응된 용액을 원심분리기(Allegra 64R, Beckman Coulter Inc., USA)로 15,000×g 조건에서 20분간 분리시켜 상징액으로 황산화 능력 분석에 사용하였다.

ABTS[2,2'-azinobis-(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonate)] 라디칼 소거능은 기존의 알려진 분석 방법으로 분석하였다(Kim 등, 2007). ABTS 라디칼 생성을 위해서 반응액(7mM ABTS와 2.45mM potassium persulfate)을 암상태에서 16시간 반응시킨 후 734nm에서의 흡광도(1.5 ± 0.02)를 맞춘 free radical solution을 시료와 혼합하여 30°C에서 반응시켜 분광광도계(DU800, Beckman Coulter, USA)로 분석하였다. 분관광도계를 이용하여 734nm에서 측정된 흡광도 값을 이용하여, 샘플 시료 무첨가구에 대한 샘플시료 첨가구의 흡광도 차이를 백분율로 표시하여 ABTS라디칼 소거능을 확인하였다.

DPPH(1,1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl) 라디칼 소거능은 알려진 분석 방법으로 분석하였다(Kriengsak 등, 2006). 분광광도계(DU800, Beckman Coulter, USA)로 흡광도를 515nm에서 DPPH working solution(1.1 ± 0.02)을 맞춘 후 1시간 동안 암상태에서 반응시켜 측정하였다. 1시간 방치한 뒤 분광광도계를 이용하여 515nm에서 흡광도를 측정하였다. 전자공여능(EDA, electron donating ability)효과로 DPPH에 대한 라디칼 소거 능력의 측정은 샘플 시료 무첨가구에 대한 샘플 시료 첨가구의 흡광도 차이를 백분율로 확인하였다.

7. 통계분석

시험구는 3품종의 과피색이 다른 토마토를 RCBD(randomized complete block design) 3반복으로 반복당 20주를 재배 관리하여, 성숙단계별로 채취된 각각의 토마토 시료(500g)을 기능성 물질 분석의 경우는 6회 반복하였고, 항산화 능력은 3회 반복하여 분석을 실시하였다. 본 실험에서 분석한 결과 값은 SAS 통계 프로그램(SAS 9.4, Institute Inc., USA)을 이용하여 분산분석으로 통계적 유의차를 검정 한 후 Duncan’s multiple range test로 95% 유의수준에서 사후검정하여 분석하였다.

결과 및 고찰

1. 성숙단계에 따른 유리당 함량 변화

본 실험에서 과피색이 다른 세 품종의 토마토 과실에 함유된 유리당은 성숙 단계 전반에 걸쳐 주로 포도당과 과당으로 축적되었다(Table 1). 이러한 결과는 광합성을 통해 토마토 과실로 전류되는 당은 자당이지만, 토마토 과실에서 자당이 분해되어 주로 존재하는 유리당은 포도당과 과당이며(Lee 등, 1972), 과실 건물중의 25%는 과당이고 22%는 포도당이라는 연구 보고(Davies와 Hobson, 1981)와 유사하였다. Beltran와 Macklin(1962)은 토마토 과실이 성숙되면서 과당과 포도당의 함량이 증가하는 것으로 보고하였는데, 본 실험에서도 이와 유사하게 황색 토마토에서는 과실 성숙과 함께 과당과 포도당이 점진적으로 증가하였다(Table 1). 반면에 흑색과 적색 토마토는 성숙 단계에서 녹숙기에서 변색기로 진행되면서 과당과 포도당이 증가하였지만 최색기로 진행되면 그 함량이 감소하였다가 다시 완숙기에서 증가되었다(Table 1). 이처럼 본 실험에서 토마토 과피색에 따라 과실의 성숙단계에 따른 과당과 포도당 축적 양상이 달랐는데, 이는 딸기 과실에서 품종의 고유한 특성으로 인하여 품종 별로 성숙 단계에 따라 과당과 포도당의 축적량이 다르다는 보고(Moing 등, 2001)와 유사하였다. 유리당의 변화는 토마토의 과피색에 따라 성숙 단계별로 다르기 때문에 과피색에 따른 품종별 관리 방법을 달리해야 할 것으로 판단된다.

Table 1.

Sugar contents according to the ripening stages in fruit of three differently colored tomato cultivars.

|

Skin color (Cultivar) | Ripening stage | Sugar (g·kg-1 D.W.) | ||

| Fructose | Glucose | Sucrose | ||

|

Yellow (cv. Sugaryellow) |

Green Breaker Turning Mature |

77.8 dz 173.5 c 242.5 b 276.4 a |

83.3 d 153.5 c 204.6 b 244.4 a |

9.3 c 15.0 a 13.2 b 11.5 c |

|

Black (cv. Sinheuksu) |

Green Breaker Turning Mature |

174.7 c 208.6 b 182.7 c 244.4 a |

160.8 c 192.6 b 176.6 c 251.3 a |

5.4 b 8.3 a 3.6 c 3.4 c |

|

Red (cv. Rapsodie) |

Green Breaker Turning Mature |

182.3 c 231.7 a 195.2 c 216.2 b |

169.1 c 207.7 a 191.0 b 205.8 a |

4.4 c 18.2 a 7.1 b 4.2 c |

2. 성숙단계에 따른 라이코펜 함량 변화

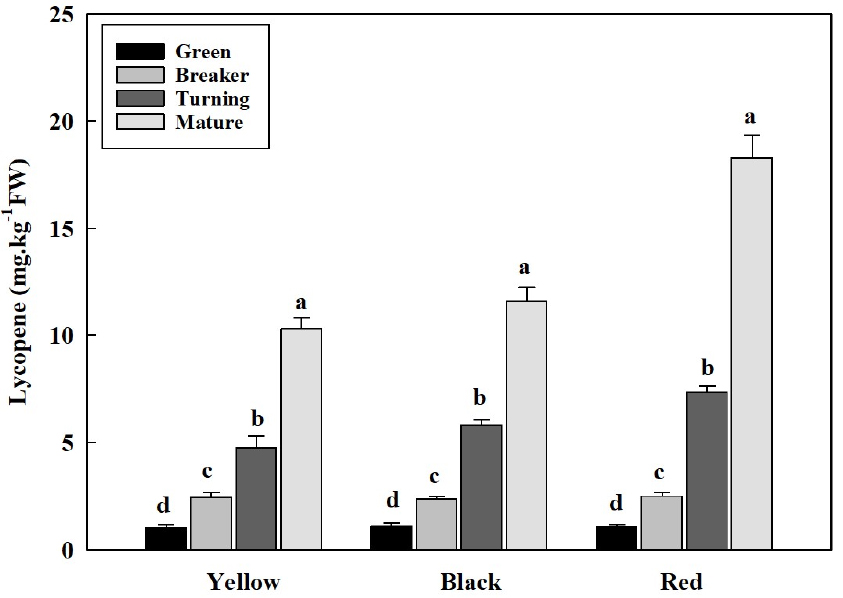

토마토의 적색 색소인 라이코펜은 식이성 카로티노이드계로 세포를 보호하고, 성숙 과정 중에 서서히 증가하여 토마토 과실을 붉게 변화시킨다(Frenkel와 Garrison, 1976; Chauhan 등, 2011; Cheng 등, 2019; Han 등, 2019; Anlar와 Bacanli, 2020). 이처럼 토마토 라이코펜 함량 증가에 따른 토마토 과피색 변화는 토마토의 수확기 판정 기준이 되기도 한다(Meredith와 Purcell, 1966; Fraser 등, 1994). 토마토 과피색에 따른 성숙단계별 라이코펜 함량을 분석한 결과 성숙이 진행될수록 증가하였으며, 또한 과피색이 다른 품종별 함량 차이가 뚜렷했다(Fig. 2). Laleye 등(2010)은 토마토가 성숙할수록 라이코펜이 증가하는 것으로 보고하였는데, 이는 우리의 연구에서 과피색이 황색, 흑색 및 적색인 토마토 모두 성숙될수록 라이코펜이 증가된 결과와 일치하였다(Fig. 2). 과피색이 다른 세 품종 모두 녹숙기와 변색기의 라이코펜 함량은 각각 1mg·kg-1과 2.5mg·kg-1정도의 수준으로 유사하였지만, 최색기와 완숙기에 접어들면서 적색 토마토의 라이코펜 함량은 황색과 흑색의 토마토에 비하여 급격하게 증가하였다. 이러한 결과는 Frenkel와 Garrison(1976)의 토마토 과실의 성숙 과정에서의 라이코펜 색소 변화에 대한 보고와 일치한다. 토마토의 라이코펜 함량은 품종이나 성숙 단계에 따라 함량 차이가 있지만(Laleye 등, 2010), 대체적으로 100g 당 완숙 토마토는 0.88에서 4.20mg이 함유되어 있고, 방울 토마토는 2.52에서 5.46mg이 함유되어 완숙 토마토보다는 방울 토마토에서 높은 것으로 보고되다(Roldán-Gutiérrez와 De-Castro, 2007).

3. 성숙단계에 따른 아스코르브산 함량 변화

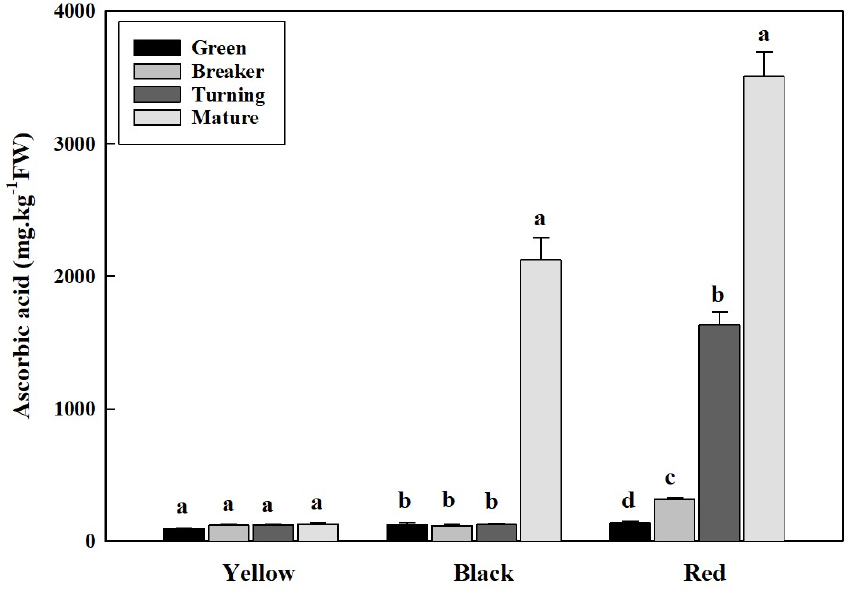

토마토 과실의 아스코르브산 함량은 재배화 과정에서 그 함량이 줄어들어 야생종에 비하여 재배종이 낮은데(Gest 등, 2013), 재배종의 경우 100g당 10-40mg 수준이지만 야생종은 재배종보다 3-5배 정도 높다(Stevens 등, 2007; Mellidou 등, 2008; Mellidou 등, 2012; Bertin와 Génard, 2018). 이러한 보고와 유사하게 본 실험에서도 과피색에 따른 품종별 아스코르브산 함량은 뚜렷한 차이를 보였다(Fig. 3). 황색 토마토의 아스코르브산 함량은 성숙과정에 관계없이 과실에 축적되는 함량이 미미하였다. 흑색 토마토 또한 녹숙기, 변색기 그리고 최색기에서는 황색토마토와 유사하게 축적되어 미미한 수준의 함량이었지만, 완숙기에서 급격하게 증가하여 2,249.7mg·kg-1으로 아스코르브산 함량이 크게 높아졌다. 적색 토마토의 아스코르브산 함량 축적 양상은 앞선 황색이나 흑색 토마토와는 다르게 성숙 4단계별로 점진적으로 증가하는 경향을 나타냈으며, 완숙기의 아스코르브산의 함량이 3,529.3mg·kg-1로 가장 높았다. 이러한 적색 토마토 과실의 성숙단계에 따른 점진적인 아스코르브산 함량 증가는 구아바(Rashida 등, 1997)나 딸기(Ferreyra 등, 2007)와 같은 원예작물에서도 유사한 경향을 나타내는 것으로 알려져 있다.

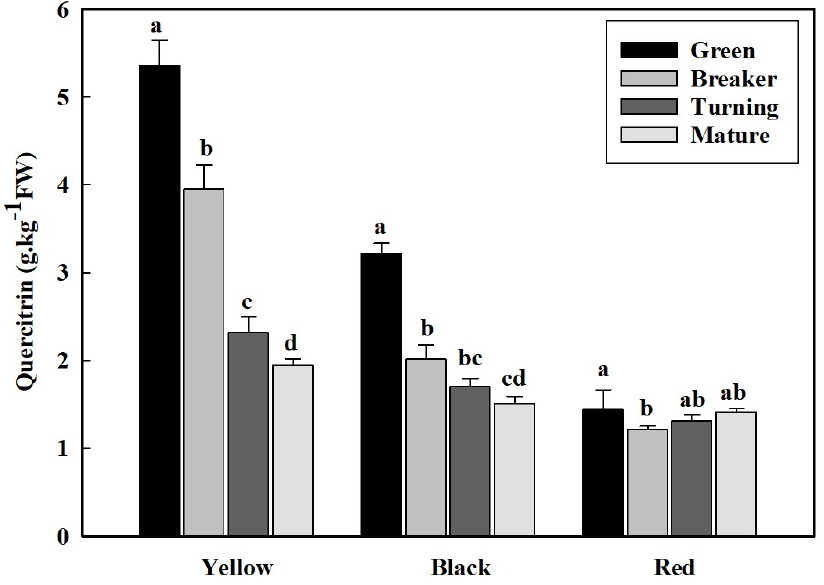

4. 성숙단계에 따른 퀘르시트린 함량 변화

환경스트레스로부터 식물의 항상성을 높이고 외부의 병원체로부터 식물을 방어하는 물질로 알려진 페놀화합물은(Hernández 등, 2009) 토마토에도 다양한 형태로 축적되는 것으로 보고되지만(Liu 등, 2012), 본 연구에서 토마토 과피색에 따른 성숙 과정 별로 캠페롤, 케르세틴 등도 분석하였지만 검출되지 않았고, 케르세틴과 데옥시당 람노오스 형태의 배당체인 퀘르시트린만이 검출되었다(Fig. 4). 퀘르시트린의 토마토 과피색별 성숙단계에 따른 축적에서, 적색 토마토를 제외한 황색과 흑색 토마토의 퀘르시트린 함량은 성숙할수록 감소하는 경향을 나타내었다. 퀘르시트린 함량이 가장 높은 것은 황색 토마토의 녹숙기 과실로 5.35g·kg-1이었다. 그 다음으로 높은 것은 황색 토마토의 변색기 과실로 3.952g·kg-1이다(Fig. 4). 흑색 토마토의 녹숙기 과실의 퀘르시트린 함량도 3.20g·kg-1으로 높은 수준이었다. 반면에 적색 토마토의 경우는 녹숙기에도 아주 낮은 퀘르시트린 함량 수준을 보였으며, 성숙하는 동안 적색 토마토의 퀘르시트린 함량 변화는 미미하였다. 이러한 결과는 토마토 과실의 캠페롤, 케르세틴, 등의 플라보노이드 화합물은 조직 및 발달 특이적으로 축적되며, 잘 익은 과실의 과육에서는 함량이 크게 줄어든다는 보고(Giuntini 등, 2008)와 유사하였다.

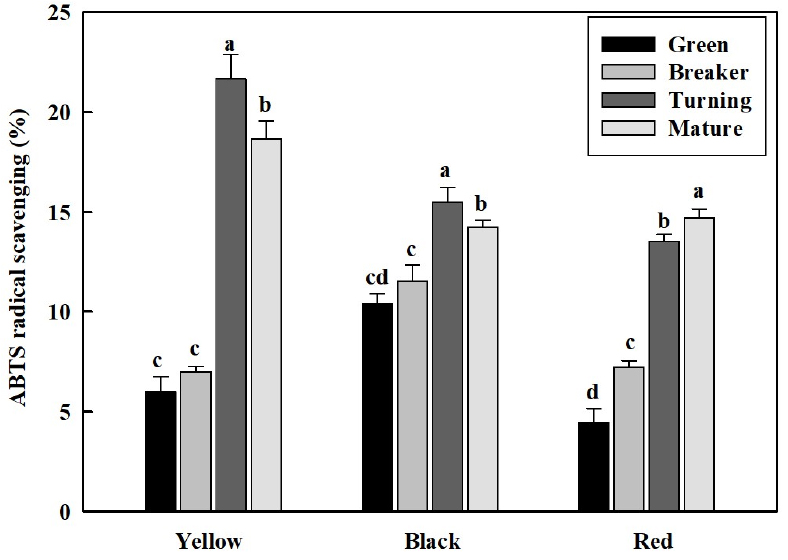

5. 성숙단계에 따른 항산화 활성 변화

활성산소종에 의한 산화적 스트레스는 DNA, 탄수화물, 단백질 등의 세포 성분에 손상을 야기하기 때문에(Gill와 Tureja, 2010), 이러한 활성산소종에 의한 손상으로부터 작물의 보호 기작을 확인하기 위해 ABTS 및 DPPH 항산화 활성 평가는 주요하게 이루어 진다(Meyers 등, 2003; Cheel 등, 2007; Fan 등, 2012). 본 연구에서 토마토 과피색에 따른 ABTS 항산화 능력을 측정한 결과 성숙이 진행될수록 증가하였다(Fig. 5). 황색 토마토의 녹숙기와 변색기의 항산화 능력(ABTS 라디칼 소거능)은 6.0과 7.1% 수준에서 최색기와 완숙기에는 각각 21.7과 19.3%로 급격하게 증가하였다. 적색 토마토의 녹숙기와 변색기의 항산화 능력은 4.5와 7.2%에서 최색기와 완숙기에는 각각 13.5와 14.7%로 증가하였다. 흑색 토마토의 녹숙기와 변색기 항산화 능력은 10.4와 11.5%로 황색이나 적색 토마토에 비해 상대적으로 높은 항산화 능력을 보였는데, 최색기에는 15.5%정도를 보인 후 완숙기에는 다소 감소하여 14.2%를 보였다.

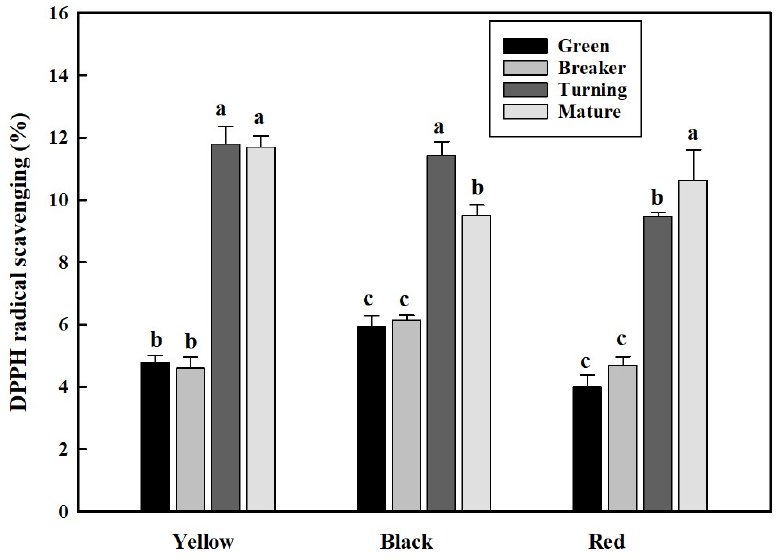

토마토 과피색에 따른 과실의 DPPH 라디칼 소거능도 ABTS 라디칼 소거능과 유사하게 성숙이 진행될수록 증가하였다(Fig. 6). 모든 품종에서 녹숙기와 변색기에 비해 최색기와 완숙기의 소거능이 높은 경향을 보였는데, 황색 토마토의 녹숙기와 변색기의 항산화 능력은 4.8과 4.6%에서 최색기와 완숙기에는 11.8과 11.7%로 증가하였고, 흑색 토마토의 녹숙기와 변색기의 항산화 능력은 5.9와 6.1%에서 최색기에는 11.4%로 증가한 후 완숙기에는 다소 감소하여 9.5%의 항산화 능력을 보였다, 적색 토마토의 녹숙기와 변색기의 항산화 능력은 4.0과 4.7%에서 최색기와 완숙기에는 각각 9.5와 10.6%를 보였다. 성숙초기에는 낮은 활성을 보였지만 성숙이 진행되어 과피색이 발현되는 최색기와 완숙기에는 높은 항산화 능력을 보인 본 연구 결과는 과피색이 적색인 토마토를 대상으로 항산화 능력을 분석한 Choi(2021)의 결과와 일치하는 경향을 보였다. 또한 성숙 시기에 따라 나무딸기에서도 항산화 활성 능력 차이가 발생하는 것으로 보고되는데(Wang와 Millner, 2009), 이는 토마토 과실의 성숙 시기에 따른 생리활성 물질의 함량 변화와 항산화 활성 능력의 차이가 발생한 본 연구 결과와 유사하였다.

결 론

토마토는 일반적으로 품종 특징에 관계없이 부피 성장이 완료된 후 성숙의 단계로 접어들면서 익어가는 과정에서 과피색이 변화하는데, 이때 과실의 성숙 정도와 과피색의 차이에 따라 생리활성 물질의 축적과 항산화 능력의 차이가 나타난다. 먼저, 과피색에 관계없이 토마토 과실에 축적되는 유리당은 주로 과당과 포도당의 형태로 존재하며, 완숙 단계에서 유리당 함량이 가장 높았다. 또한 과피색에 관계없이 모든 토마토 과실의 라이코펜 함량은 완숙 단계에서 가장 높았으며, 특히 적색 토마토의 라이코펜 함량이 황색이나 흑색 과실보다 완숙기에 월등히 높았다. 반면에 아스코르브산은 품종별 차이가 크게 나타냈는데, 황색 토마토 과실에서는 미미하게 축적되었으나 흑색과 적색의 토마토 과실에서는 완숙 단계에서 함량이 급격하게 증가하였다. 또한 퀘르시트린은 주로 과실의 성숙 초기인 녹숙기에서 함량이 높았으며, 익을수록 줄어들었다. 마지막으로 토마토 과실의 항산화 능력과 과피색과의 관련성은 크지 않으며, 주로 성숙 초기보다는 성숙 후기에 항산화 활성이 높았다.